“All nature in its myriad forms of life is changeable, impermanent, unenduring. Only the informing principle of nature endures. Nature is many and is marked by separation. The informing principle is one and is marked by unity. By overcoming the senses and the selfishness within, which is the overcoming of nature, we emerge from the chrysalis of the personal and illusionary and fly into the glorious light of the impersonal, the region of universal truth, out of which all perishable forms come.” 1

James Allen

The world we perceive exists in space and time. Everything that comprises the world comes into existence as a form subject to space and time and perishes in time and space. Nothing lasts forever.

Observation, however, reveals that the comings and goings of those appearances repeat their cycles infinitely. Life forms change yet life continues.

Kant conceived that there are two worlds: The ‘real’ world (the thing in itself) and the ‘apparent’ world (the world of ‘phenomena.’) 2

He saw space and time belonged only to the plane of phenomena as forms of perception.

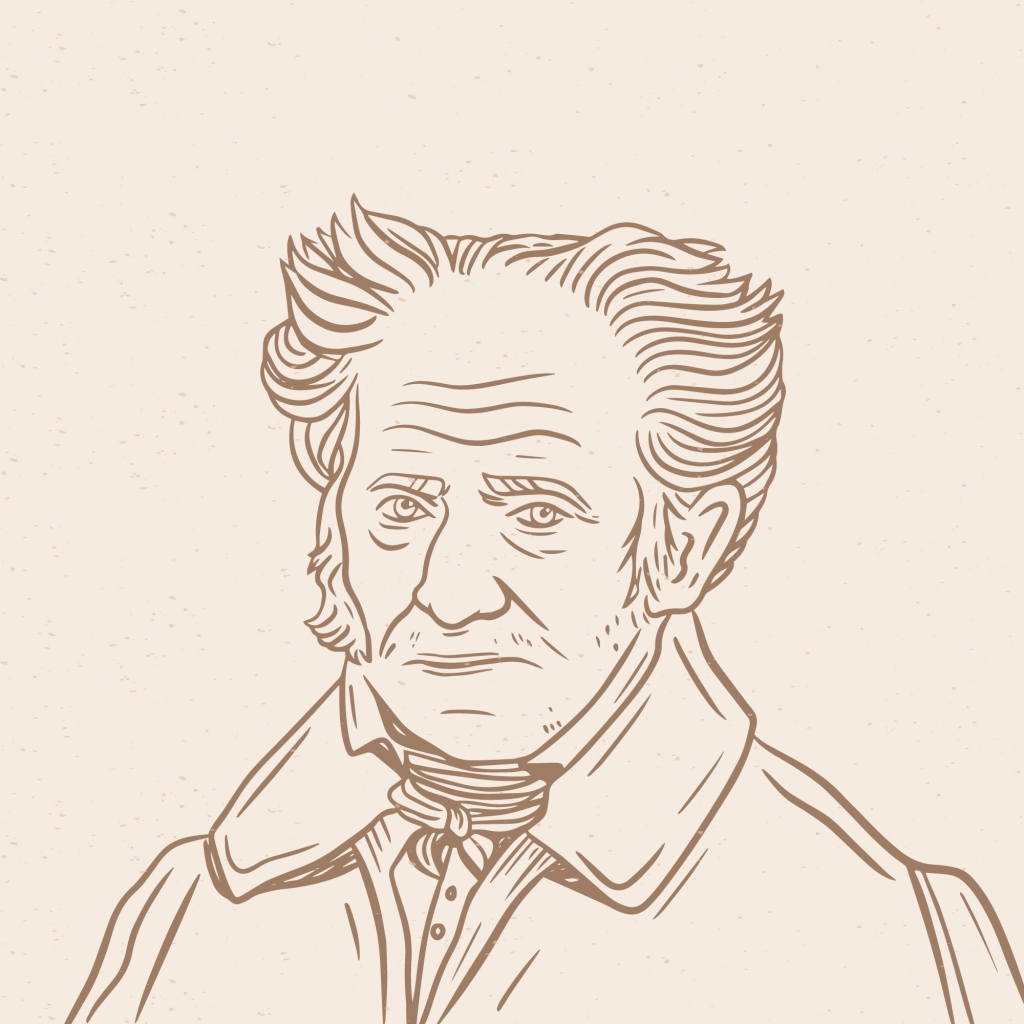

Schopenhauer further developed Kant’s understanding. He contemplated that the world is duality: The world as ‘idea’ and the world as ‘will.’

For him, the former is the outer, physical world, the realm of time, space, and causation. This is Kant’s phenomenal world.

The latter is the inner, subjective world, the realm not subject to the forms of space and time, a unity, and ‘reality.’ This is Kant’s noumenal world, ‘the thing itself.’

Why is it that philosophers have been contemplating analogous subjects over and over? Maybe it’s because they penetrated perpetual truth despite transient appearances, I ponder.

We collectively may have needed a guiding and enduring principle just like a lighthouse illuminating the dark sea at night to give meaning to our temporary existence. For this transient phenomenon called life hasn’t seemed like a true reality to us.

Plato says to Glaucon in the Republic:

‘I call anything that harms or destroys a thing evil, and anything that preserves and benefits it good. … Then hasn’t each individual thing its own particular good and evil? So most things are subject to their own specific form of evil or disease; for example, the eyes to ophthalmia and the body generally to illness, grain to mildew, timber to rot, bronze and iron to rust, and so on. … A thing’s specific evil or flaw is therefore what destroys it, and nothing else will do so. For what is good is not destructive, nor what is neutral. … If, therefore, we find anything whose specific evil can mar it, but cannot finally destroy it, we shall know that it must by its very nature be indestructible.’ 3

What is indestructible? As philosophers have long contemplated observing the nature of the world, the invisible, inner, subjective world, the unity that transcends time and space might be so. And they are rightfully considered real.

As in James Allen’s beautiful passage, the enduring principle that is marked by unity may be the reality, the in-forming principle out of which all perishable forms come.

Jay

Note:

1. James Allen, From Poverty to Power, 1901

This book is included in ‘As a Man Thinketh, Tarcher/Penguin Edition, 2008.

Quoted passage in Entering Into the Infinite, The Way of Peace, From Poverty to Power, p183

2. Introduction of Essays and Aphorisms (by Arthur Schopenhauer) by R. J. Hollingdale, 1970, page xxii~xxv

The world exists as we perceive it. Kant conceived that this world (we perceive) is not reality because the mind imposes a certain structure upon the world in order to apprehend it. He believed that there must exist a ‘real’ world ‘before’ and ‘independent of’ the imposition of (the categories of) reason. For him, the world perceived under the forms of categories (such as reason) was ‘appearance’ or ‘phenomena.’ Also, space and time belonged only to the plane of phenomena as forms of perception.

Essays and Aphorisms, Penguin Classic, 1970:

This book is a translation by R. J. Hollingdale, 1970, of Parerga and Paralipomena – a selection from Schopenhauer’s last writings: the collection of essays, aphorisms, and thoughts to which he gave the name Parerga and Paralipomena, published in 1851.

3. The Myth of Er, Part XI: The Immortality of the Soul and the Rewards of Goodness, The Republic. Translated by Desmond Lee, Penguin Books, 2007.